Just as bell hooks advocates “an oppositional gaze” that highlights the unique experiences of African American women compared to white women, in “Difference: A Special Third World Women Issue,” Trinh T. Minh-ha emphasizes that the challenges faced by women in developing countries differ from those encountered by Western white women. Trinh T. Minh-ha argues that for women in these regions who face both colonial and gender oppression, silence serves as both a means of self-expression and a form of resistance.

Unlike untirelessly and passionately rewriting women’s history, Trinh T. Minh-ha argues that presenting history from a woman’s perspective is just the beginning. More importantly, she emphasizes the need to suggest new directions for the present. Trinh T. Minh-ha echoed Barbara Smith’s sentiments: “Feminism, is the political theory and practice that struggles to free all women . . . Anything less than this vision of total freedom is not feminism, but merely female self-aggrandizement. “(Smith, 1982)

Trinh T. Minh-ha envisions that an overemphasis on putting an identity to women simplifies complex individuals, especially the third world women. The approach erases differences and overlooks the distinction between identity and difference. A proactive way to counteract hegemony and patriarchy is to embrace diversity. Drawing from her own identity and experiences, she emphasizes the plight of women in the third world. Trinh T. Minh-ha notes that Western feminists often claim ignorance regarding third world women’s perspectives while neglecting to actively seek them out. Feminist studies from the third world represent a unique category, a serious leak requiring filling and development.

I appreciate Trinh T Minh-ha’s prudent and proactive attitude, in which she places the female (the second sex) of the third world in a subversive and non-aligned position. She use of the term “third world” is also a form of identity, while She recognizes multiple areas and cultures in the same identity of “the third world.” The differences and diversity outweigh the identity. From this point of view, I, as a woman from China, am undoubtedly interested in the situation of Chinese feminists, feminist films, and the development of feminism. After reading Trinh T. Minh-ha’s article, I believe it is essential to place the differences, including class, gender, and region, in feminist studies.

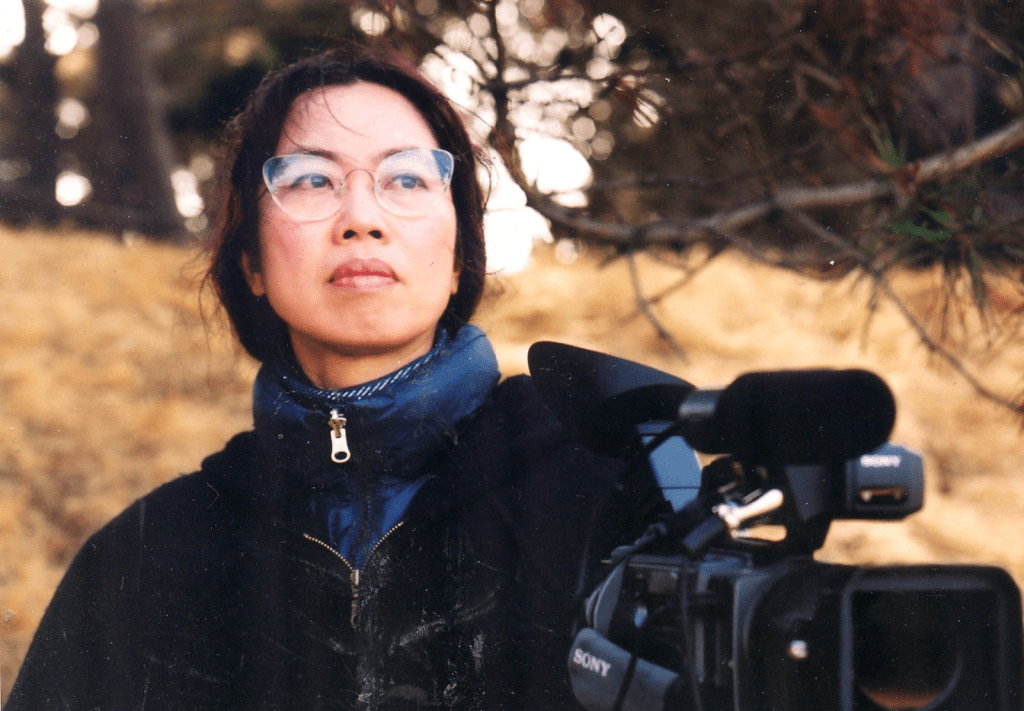

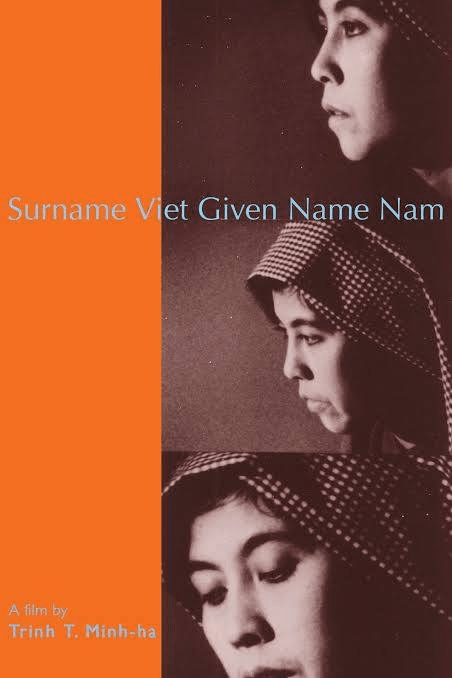

Last but not least, Trinh T. Minh-ha’s films strengthen her opinions. Just as Hottell notes that feminist filmmakers like Trinh T. Minh-ha and Julie Dash express their beliefs and theories through their cinematic works, Trinh T. Minh-ha illustrates the differences and identities of the third-world subject through fictional narratives and varying perspectives. Her concept of “Don’t speak about, but speak nearby” embodies a dynamic approach to portraying the lives of third-world women. Furthermore, Trinh T. Minh-ha challenges traditional documentary and feature film norms, allowing her films to exist in a space between fiction and authenticity, which conveys the identities and distinctions among women in the third world. For example, in “Surname Viet, Given Name Nam”(1989) , she designs her four interviewees based on real experiences from both South and North Vietnam. Despite their significant differences, they all share the common experiences of suffering from war and patriarchy. This distinctive form of filmmaking, which is challenging to classify, can be described as ethnographic feminist films, experimental ethnography, or essay films, and has also inspired many feminist filmmakers.

Reference:

Minh-ha, Trinh T. “Difference: ‘A Special Third World Women Issue.’” Discourse 8 (1986): 11–38.

The photos resource: https://www.wmm.com/catalog/film/surname-viet-given-name-nam/

Leave a comment