In the article “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus,” Baudry explains that cinema imitates “perspective artificalis” and that projection transforms differentiated frames into a continuity of movement, immersing the viewer in an illusion. He argues that ideology is reproduced through the apparatuses of cinema. This ideological effect is accentuated through the three phases of cinema: filming, projecting, and viewing.

The School of Athens

Raphael

1509–1511

During filming, the “subject-eye” serves as the camera’s focal point. Renaissance paintings utilized perspective, a principle that the camera imitated, to create a three-dimensional space that provides the viewer with a center point to appreciate paintings. This imitation allows the camera to not only produce a realistic illusion but also to define the center viewer’s status of observation. The eye-subject, guided by the camera’s movements, elevates each frame and establishes the “objective reality”. In the projection stage, by diminishing the separations and discontinuities present in films, the film projection creates a visual continuum that immerses the spectator in the constructed ideology of the film. From a viewing stage, Baudry likens the darkened theater and the projector to “Plato’s Cave.” These elements form the necessary scenario for Lacan’s “mirror stage.” The infant sees a mirror image of itself and thus develops an imaginary self. At this time, the infant’s eyesight has matured, but its mobility has not yet fully developed, similar to the spectator sitting in the theater. The spectator first identifies with the camera as a transcendental subject, and then the spectator, seated in a completely dark and enclosed viewing environment, identifies with the images made visible by the camera and projector.

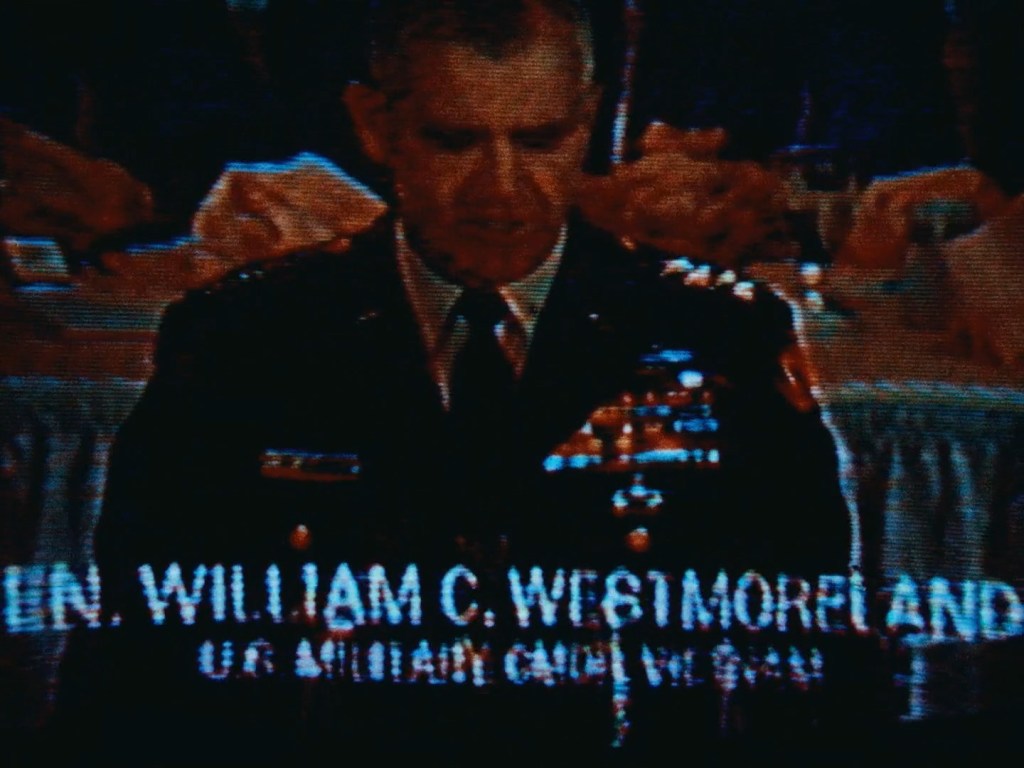

Screenshots from Far From Vietnam (1967)

The basic cinematic apparatuses unconsciously force the audience into the film’s world, fostering belief in the illusions crafted on screen. A primary reason is the continuous narrative illusion that makes the cinematic apparatus invisible. Nevertheless, Baudry points out in the last part of his essay that once the audience recognizes the apparatus’s existence, the ideological impact collapses. He states, “Both specular tranquility and the assurance of one’s own identity collapse simultaneously with the revealing of the mechanism, that is of the inscription of the film-work.” (Baudry,1970) A segment from “Why We Fight” in Far From Vietnam (1967) offers an example to Baudry’s theory. The segment shows that the camera records a television broadcast in which the US government defends the legality of US troops in Vietnam. The director applies an analog distortion effect, causing the footage to appear pixelated, blurred, and distorted, which heightens the disjunction between segments and conveys a purposeful intention. The director implies that news coverage distorts reality by exposing the apparatuses that degrade image quality, revealing the ideological effects lurking beneath the surface and encouraging the audience to engage critically with what they witness.

A significant strength of Baudry’s theory is that it liberates film theory from film ontology and montage analysis, focusing instead on the technical base of cinematic apparatus and the physical spaces of cinemas. Although his approach broadens film theory, Baudry does not thoroughly explore the complexities of the term “ideology” as defined by Louis Pierre Althusser. The concept of “ideology” includes various political, cultural, and national aspects interpretations. Rather than addressing these intricacies, Baudry adopts a vague definition of “ideological effect,” neglecting to distinguish the varying ideologies portrayed by different cinematic apparatuses during the filming, projecting, and viewing stages. Moreover, Baudry fails to recognize the power dynamics present in both the filming apparatus and its content. As a filming apparatus, the camera determines what the spectator can watch and commands the power of the gaze. Thereafter, the inherent gaze of the camera has been thoroughly analyzed by subsequent feminist theorists.

Leave a comment